Causal inference yesterday, today and tomorrow: a talk by Ilya Shpitser, Johns Hopkins University

My notes on select parts of the talk, in particular, what Machine Learning and Causal Inference communities can learn from each other.

The content of this post is based on a lecture given by Ilya Shpitser. The ideas presented are his. This post reflects my personal interpretation and understanding of the material. Any errors or omissions are my own.

Recorded at Perimeter Institute, as part of a monthly webinar series jointly hosted by Perimeter, IVADO, and Institut Courtois: https://pirsa.org/24090157.

Causal inference

In causal inference, we imagine different “what-if” scenarios—what if an intervention happens, what if it doesn’t—and study the potential outcomes that might result from each scenario to understand the cause-effect relationship.

Top-down and bottom-up approaches

Consider two luminaries from the 1740s: David Hume and James Lind. David Hume was a methods person, sitting in his armchair, like a philosopher does, trying to figure out a good definition of causality. James Lind was an applications person, running the first ever randomized trials to find the cure for scurvy.

These two people exemplify the two approaches to causal inference: top down and bottom up.

Modern causal inference is a partnership between methods people and applications people. You need both because if you’re an applications person and you don’t have rigorous theory, you can do the wrong thing. And if you’re a theory person, without applications, you can go off in directions that aren’t connected to any real problems.

Some terminology & notation

In causal inference, we want to understand the effect of a particular action or intervention (the cause) on an outcome (the effect).

We conceptualize cause-effect relationships by means of (random variable) responses to hypothetical interventions (also known as a counterfactual

There are various notations for this, one of which is \(Y(a)\)

Note that it is very different from \(Y\vert a\) which reads “\(Y\)—if we observed A—to have value \(a\)”. This distinction is a mathematical reflection of the familiar saying that “correlation is not causation”.

The way people think about cause-effect relationships is in terms of hypothetical interventions that set a cause whose effect we’re interested in to a particular value (hypothetically), set it to a different value (hypothetically), and compare the outcomes. This is useful in real-life scenarios, where you are unable to do randomized trials. So you do this kind of special massaging of the data, which we call adjusting for confounders.

Schools of thought

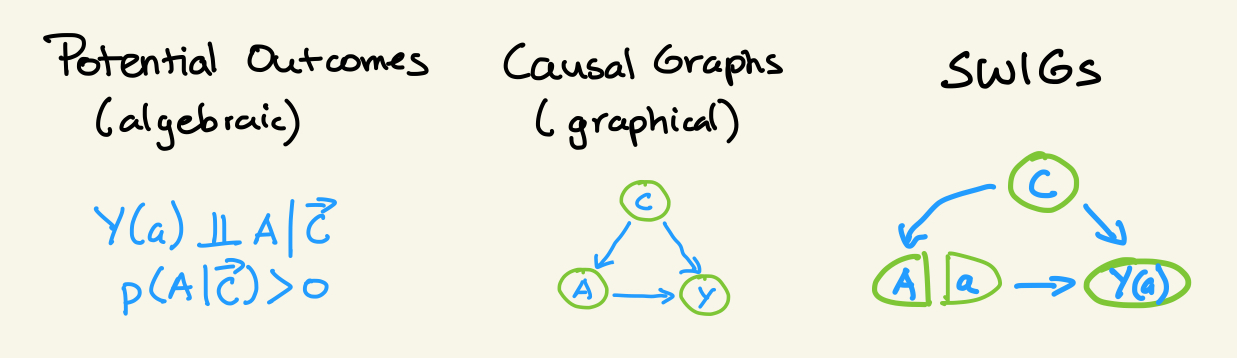

There are at least two schools of thought on Causal Modelling: Potential outcomes and Causal Graphs. Potential outcomes specifies causal assumptions algebraically, emphasizes (potentially counterfactual) random variables, and is common in statistics and public health. Causal graphs specifies causal assumptions graphically, emphasizes operators (eg the do() operator) and structural equations, and is common in computer science (and CMU

The modern causal inference pipeline

(From Ilya’s POV)

Start by talking to somebody who does applications, come up with a cause-effect question of interest, then try to express it mathematically in terms of a causal parameter, usually as a hypothetical experiment, such as the average causal effect

Elicit a causal model—which encodes assumptions we’re willing to make about the problem—from an expert, or possibly learn the model from data.

Do identification, which means asking if a causal parameter can be uniquely expressible in terms of available data given the causal model. This is basically checking that the observed data likelihood that we have in the problem actually has information that can be brought to bear on what we’re asking. That’s very important.

If the parameter can be expressed in terms of observed data, we think about estimation, or statistical inference, or learning (if we’re a machine learning person). This means we ask how we can construct a procedure that makes a good guess about our identified parameter from data. We might be concerned with doing it efficiently or doing it robustly.

Causal parameters are generally counterfactual. Because of this, it’s very difficult to validate whether we did a good job estimating them (unlike in machine learning and supervised learning problems where validation can be accomplished using, eg, holdout data

Quantifying uncertainty is important, which can be done by confidence intervals or credible intervals.

Connections between causal inference and missing data

Causal inference is a version of a missing data problem. Vice versa, you can think about missing data problems causally.

In causal inference, the fundamental object is:

What would be the outcome if, hypothetically, I set the treatment to some value, possibly contrary to fact.

In missing data, we are interested in:

What would be the outcome if we could hypothetically observe it, even though in reality it may be missing.

The principled methods from missing data have a strong relationship to principled methods from causal inference. They are kind of sister disciplines.

What Machine Learning and Causal Inference communities can learn from each other

Constructive optimism vs. constructive pessimism

Machine learning (ML) is a very optimistic field. They have a “let’s just build it and see if it works” attitude, even if they can’t prove it will always work, which is admirable. They publish quickly and often, and the progress is clear, as the recently-developed large language models (LLMs) have shown.

Causal inference (CI) people, on the other hand, are conservative and constructively pessimistic. Since it’s difficult for them to validate their results, they assume that they are wrong by default. They spend a lot of time thinking about: robust methods; validation; sensitivity analysis (checking if violating their assumptions still gives them the answer they expect). This is a valuable attitude in applied problems, where things don’t work the way you would expect.

Finite sample vs. asymptotic results

ML people tend to think about finite sample results. CI people tend to think about asymptotic identification and estimation results. These are good complements to each other

Validation vs. transparency

People in ML emphasize tasks and validation of results, which is very useful. On the other hand, people in CI aren’t able to validate their findings (you can’t observe things that didn’t happen), so they try to be very transparent about their assumptions and put them upfront. Both are very important to how we should do science.

Semi-parametric theory and predictive performance

Causal inference people know that often the best way to approach problems with infinite-dimensional parameters is to use semi-parameteric theory. A lot of folks in ML aren’t aware of this. Ilya believes that semi-parametric theory is the correct approach for many problems that arise in ML, such as problems in model based reinforcement learning for example.

In saying that, people in ML have thought about predictive modelling really hard for the last 50 years and they have excellent predictive performance. This can be very helpful as a subroutine for semi-parametric

Parameter identifiability

People in CI worry about parameter identifiability, which is the very important problem of determining if your data has information about your problem. In ML, there are some model fragility issues related to the fact that parameters in ML are not identified because the models are over-parameterized (deep learning systems have billions of parameters).

Unsupervised problems

CI isn’t a supervised problem, so CI people have developed principled ways of thinking about problems that are unsupervised. Many problems in ML also go beyond the traditional supervised framework, even though they are sometimes approached as if they were purely supervised. For example, in a prediction task, if some outcomes are unobserved, this becomes a missing data issue, which shifts the problem away from a strictly supervised setting. Acknowledging these nuances can help both fields refine their approaches.

Causal language

Causal language is very helpful when thinking about model stability, invariance, fairness, interpretability. This has been noticed in a lot of ML papers that use CI.

Missing data

CI and missing data are sister disciplines, so causal methods give you principled approaches for thinking about missing data. This is particularly important since most applied analyses will inevitably encounter some degree of missing data. In practice, it’s common to see quick fixes, such as using a standard imputation package in Python or R. But it’s crucial to go beyond thinking of missing data as a data cleaning issue. Different types of missingness require different strategies.

Powerful optimization methods

People in ML have powerful optimization methods which are likely helpful for solving estimating equations that arise in semi-parametric inference.

Surprisingly many, but not all, problems are regression problems

A big lesson from ML is that surprisingly many problems in life are regression problems, which neural networks are well-suited to handle.

But it’s important to acknowledge that not every problem can be approached as a regression problem. While LLMs have generated excitement due to their impressive capabilities, there’s a growing realization that they have limitations. For example, LLMs can sometimes produce misleading or overly optimistic responses and may struggle with highly structured problems, such as proofs, chess, or tasks involving causal inference. This isn’t surprising, as different types of problems—like planning, logical reasoning, and causal inference—have specialized methods that are better suited to their unique demands. LLMs, despite their advanced transformer architectures, are not designed to excel at every type of problem, and it’s important to apply the right tools to the right challenges.

The elevator pitch for why we do causal inference

Causal inference can be used to emulate randomized control trials in cases where its either unethical (like medicine) or too expensive (like in economics

But it’s not like you get this for free. You get this by making assumptions about the causal model. Those assumptions might not be exactly right so you have to be upfront about your assumptions and pitch your result as: if you believe this list of assumptions, then this is our conclusion, but if you do not, then you should believe it less.

What else did Ilya cover in the talk that didn’t make it* into my notes?

(*not because it’s any less interesting, just not where my head is at right now)

- The state of the art in causal inference

- An example of the causal inference pipeline on a project he is working on with cardiac surgeons

- Open problems in causal inference

- State of the art with “post-selected data”, which means something different in causal inference and quantum information communities (during question time)

- Areas for collaboration between ML & CI (during question time)

- How causal language lets you assess stability (during question time)

Should you watch the talk?

It’s a really nice talk. I recommend it. You can watch it here.